archives > to > archives: mining library collections for new additions to the People’s Graphic Design Archive

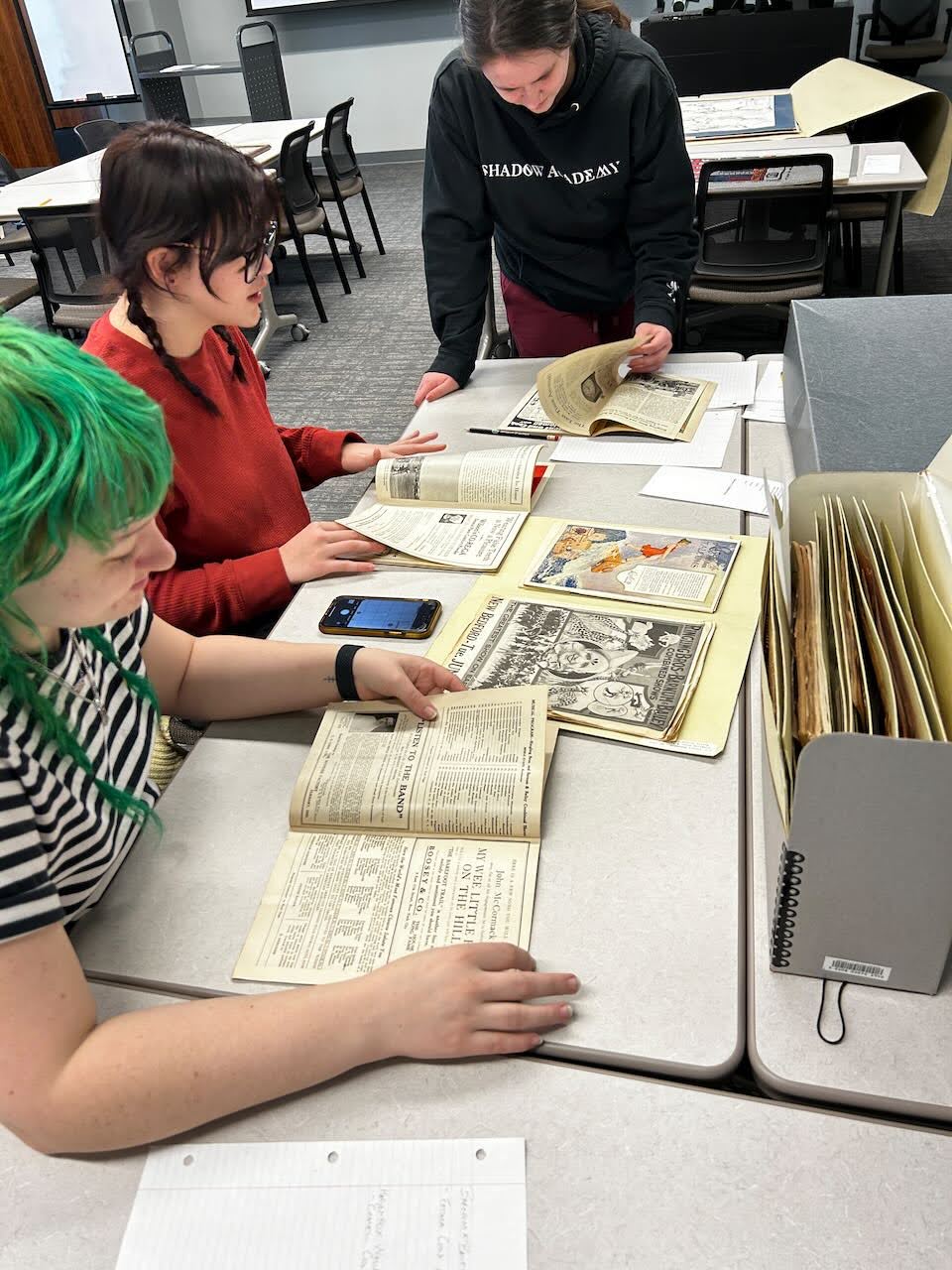

University of Georgia typography students, guided by Julie Spivey, review materials held in the campus Special Collections Library.

The University of Georgia community is fortunate to have extensive Special Collections Libraries, including a large collection of artist and small press books in the Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscripts Library.

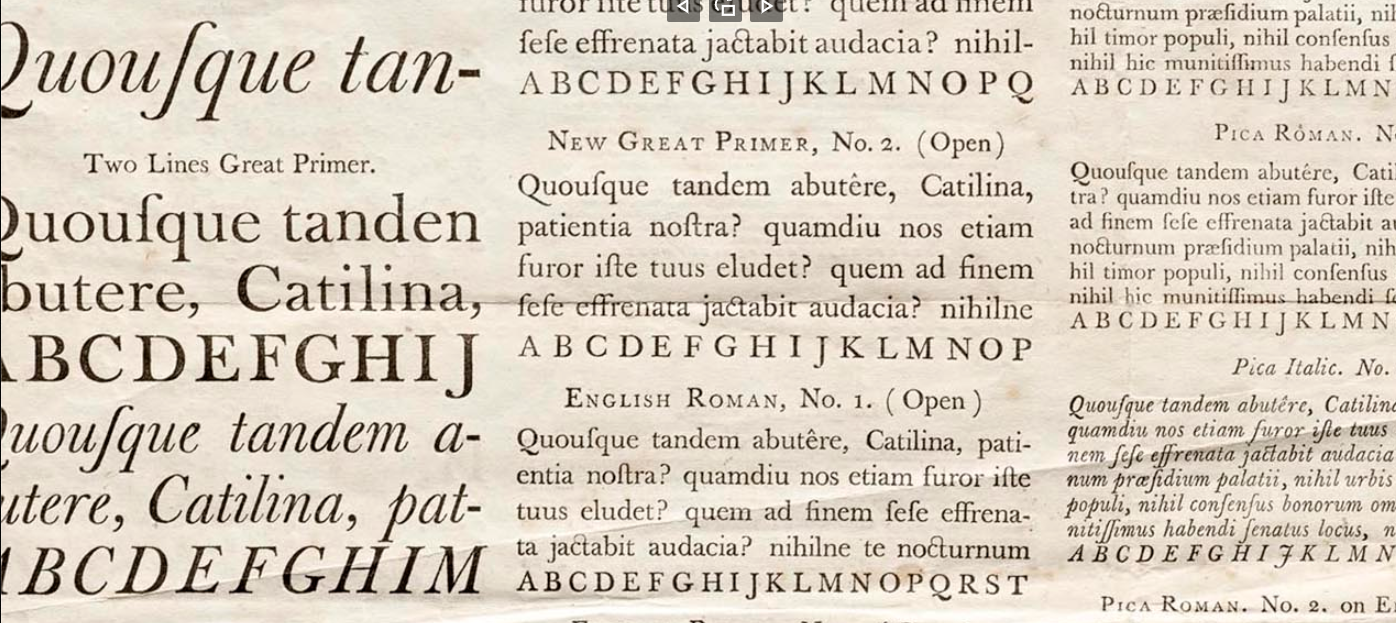

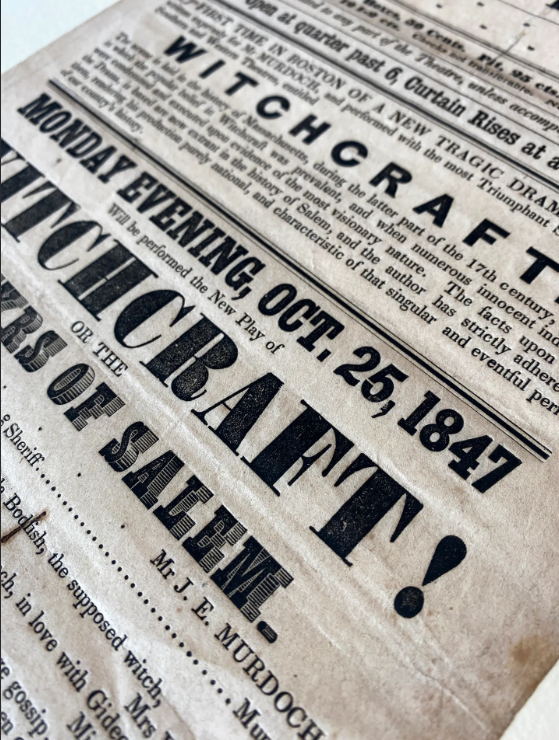

Beginning in 2023, through UGA’s Special Collections Fellows program, I began to integrate more archive-based learning into courses. During the fall term, our Typography 1 students engaged with a curated collection of objects focused on typographic history, nomenclature, and categorization. The collection included items such as a 1785 specimen of printing types from a London type foundry and an 1847 Boston theater broadside for a play about the Salem witch trials, featuring fonts from nearly every historical category, including sans serif.

A Specimen of Printing Types, Joseph Fry & Sons, London (1785). See on Letterform Archive.

Students were highly engaged as they handled the pieces and experienced their weight, texture and print impressions firsthand. This direct interaction facilitated a better understanding and application of typographic terminology and historical classification. Working with physical artifacts of visual communication also provided a meaningful contrast to their extensive experiences with and in digital media. Recently, there has been a noticeable increase in students’ unfamiliarity with physical artifacts and their tactile characteristics.

“Witchcraft, or the Martyrs of Salem” National Theatre Broadside, Boston. 1847

Exploring such collections reveals the irony of archives: while many fascinating objects and potential visual treasures are safely protected, they are also kept hidden from view. This is particularly true for compelling visual works or pieces of graphic design, as the majority of searchable information consists primarily of descriptive text, typically limited to the subject matter.

In spring 2024, I asked my graphic design students to explore the library archives to select items they believed would be valuable contributions to submit to the People’s Graphic Design Archive. The students in this second-year major studio course were already familiar with our Special Collections Libraries from the fall Typography course experiences so they understood basic care and handling of artifacts.

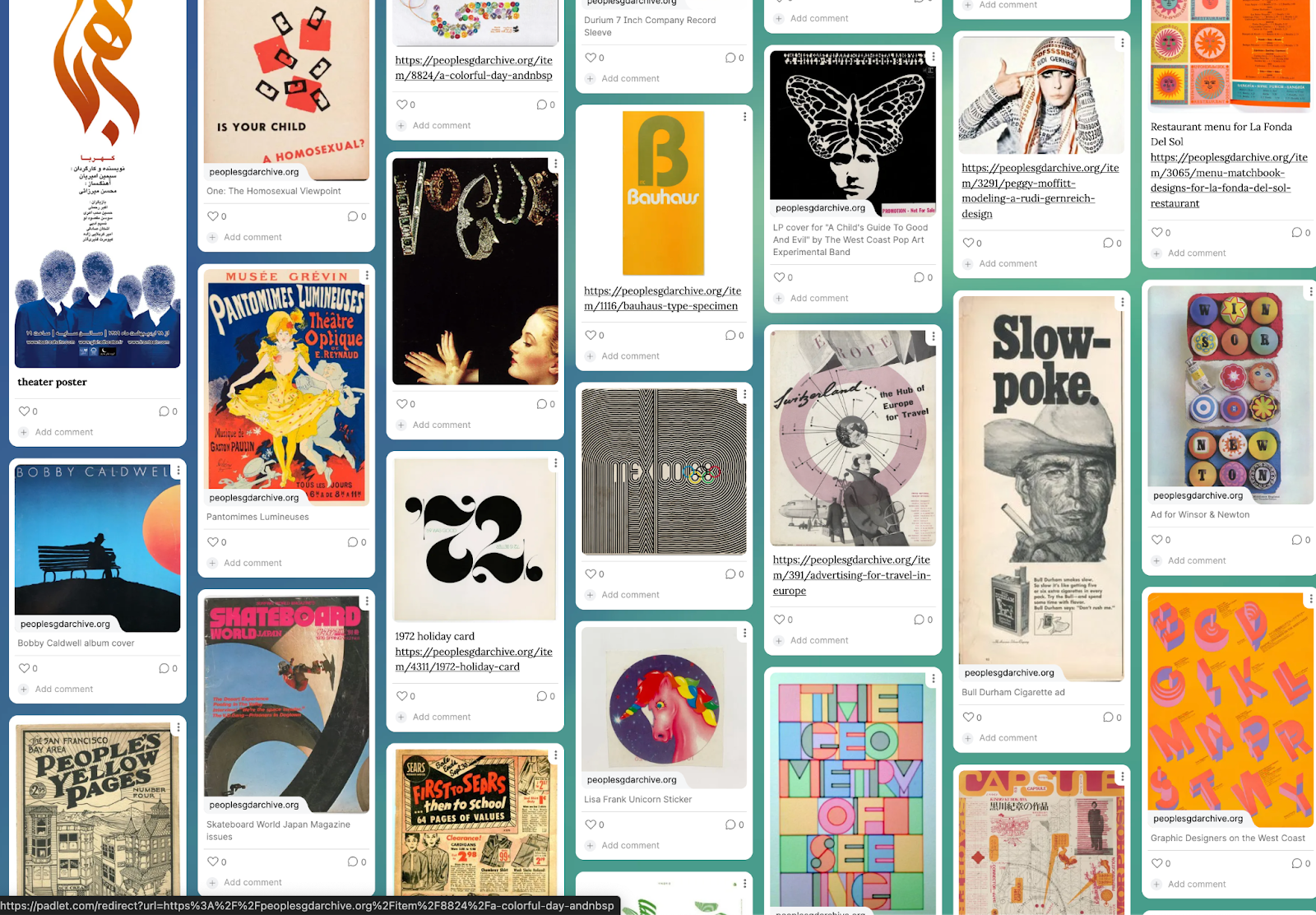

First, we familiarized ourselves with the PGDA, including creating a visual archive collection of the students’ favorite pieces in a shared digital space. We reviewed PGDA resources about adding to the archive and best practices for tagging and keywords.

Our initial visit to the library focused on reviewing a curated selection of objects to illustrate the broad range of artifacts available, beyond the more focused grouping they had encountered previously. We were fortunate to work with a dedicated and knowledgeable librarian who demonstrated how to utilize the library’s finding aids to search the collections and request objects from the archives.

Before our second visit, each student had researched and requested an item for review. We had compiled and submitted our requests ahead of time so the items could be retrieved from the vaults and ready for our visit. (No more than one object per person could be requested and pulled for each visit, as the objects are stored in climate-controlled vaults and each must be retrieved. But the students could also visit the library outside of class and have items retrieved like any other patient patron.)

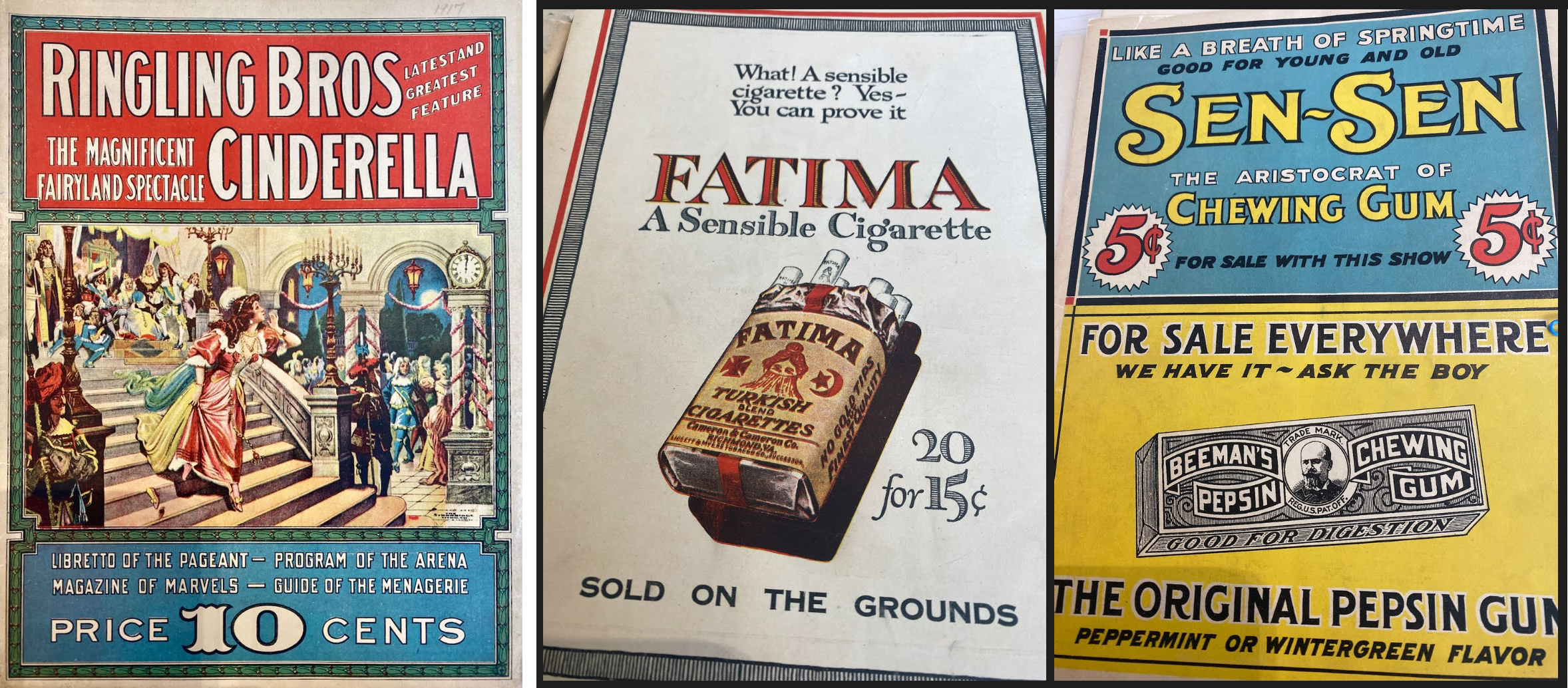

Reviewing the pieces revealed a wide variety of artifacts: some students excitedly found that their object was even more appealing than they had envisioned, but then other items turned out to be duds (the librarian’s term). In other cases, students discovered entirely different and unexpected items, especially in boxed collections, like these ads found in early 1900s circus programs: researched by Rayne Cross.

The objects the students ended up choosing ranged from an illuminated page from a 15th century prayer book to a promotional program for the Danish opening of the film, To Kill a Mockingbird, to issues of the WWI-era French illustrated journal, Le Mot. View some uploads here:

French Book of Hours researched by Anna Pham

Le Mot magazine researched by Gabby Branch

Danish movie program for To Kill a Mockingbird researched by Gabby Branch

The students discovered that searching for visual objects in archives can be challenging because items are cataloged by content and topic, catering primarily to traditional researchers. Entries provide little information on visual design or approach, often noting only format and dimensions. Even common terms like “poster” may yield few results, since archives frequently using alternative terms like “broadside.” The searchable information and keywords tend to focus on topics, organizations, and individuals, often lacking details about the artifacts as examples of visual communication or design.

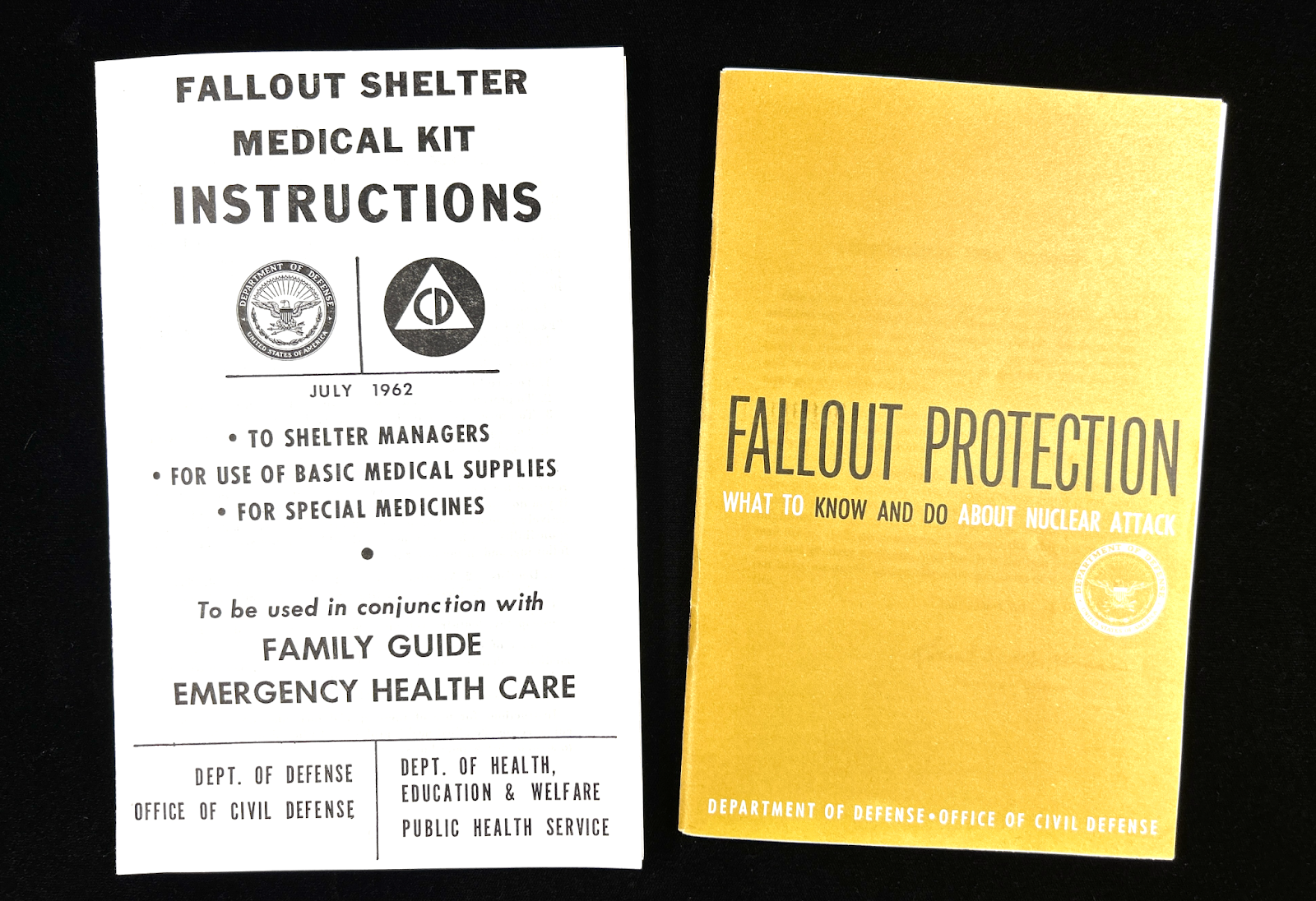

For example, these 1962 Department of Defense publications related to nuclear attack preparation were found among the vast collection of personal papers of a Georgia-born U.S. Secretary of State, but the finding aid entry doesn’t indicate such materials. One just has to sort through lots of boxes.

Our Challenges

Since items cannot be removed from the archive reading rooms, capturing imagery was a challenge in some cases. For small items on a sunny day, we might be able to take an acceptable photo ourselves if positioned next to a window. In other instances, students were able to find decent images of their items in other online archives or auction sites. The library can provide limited image services for some large items, but this typically requires more lead time than we had.

What I learned for next time:

For some selected artifacts, minimal information was available about the work. This is understandable given the historical nature of the pieces and the anonymity of many designers and early commercial artists.

For other submissions, students identified much more information related to the works than we ultimately included. This was due to conflicting sources or the inability to confirm the accuracy of the information at a level we felt comfortable posting (within our time constraints). Next time, we will allow more dedicated class time for content research and for refining the accompanying posts.

Additionally, I found myself wishing for a PGDA teacher-level admin account. While posts should be created by students and remain under their ownership, having access to edit minor details, such as missing tags, would have been helpful and more efficient, especially after a course is completed and students have moved on.

Julie Spivey is a designer and educator with a particular fondness for letterforms, typography and effective information hierarchy. She is Professor of Graphic Design in the Lamar Dodd School of Art at the University of Georgia and a former co-chair of the Steering Committee for the AIGA Design Educators Community.