Tagging the People’s Graphic Design Archive

“User-generated content” is an awful term. Used to describe tagging in commercial and social media sites, it sounds like what ends up in a trash receptacle at a playground. In the professional information studies world, the terminology only gets worse: metadata ecosystems within multifaceted artifact description anyone? Marketing people are happy to have users promote their goods with free labor. But whether in commercial and academic circles, user contributions generate real value on the basic principle that “discoverability” is enhanced by adding tags to content. Still, some tags may be more useful than others and so here are a few thoughts on the process.

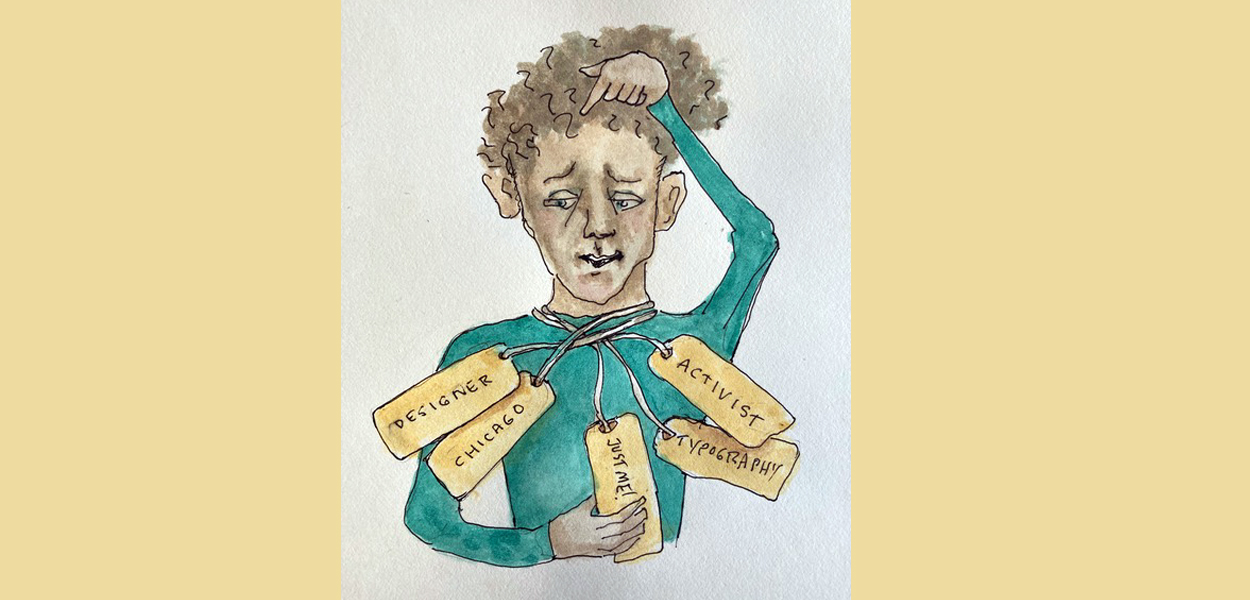

A collection the size of the People’s Graphic Design Archive is just too large to look through in its entirety, especially if you are looking for specific materials. Tags serve to sort the mass of stuff into smaller groups. The application of individual knowledge is a gift to others. Your observation may bring a feature to the surface and pull it into view. But consider the various kinds of tags. They may all look the same but serve different purposes.

Types of tags

- General Description: A tag can be a descriptive label: magazine, poster, movie titles. At that level of generality, the tag identifies a capacious class of materials related by a single factor—their genre, format, or other feature. These are general categories or “high-level” classifications. If you are looking for political protest art or underground publications, these might not be of much assistance.

- Narrow categories: A tag can identify a more specific category of items: hand-drawn type, newsprint, or digital photography. These are definite categories though they might contain many specimens. These tags work well for identifying processes, production methods,

- Proper names: These tags have no ambiguity in them and often consist of proper names: ReVerb, Atlantic Records, Marilyn and John Neuhart, collection of Brockett Horne.

- Value judgments: A tag can be a pointer, calling attention to something that requires judgment or evaluation: hardcore, grunge, and other style or movement terms

- Specialized information: staple-bound, Wicca, women’s suffrage, labor history. These should call attention to properties of a work that might not show up in the other categories otherwise but have research value. Looking through every publication in PGDA to find materials related to such a specialized topic would be daunting.

Fan tagging graphic design

In the case of PGDA, the activity resembles fan-based tagging rather than marketing or promotion. The point of tags in the Archive is to share expertise, make objects visible through a search, and make them useful for researchers, teachers, or others who would not find them without the tags. Fan tagging is distinguished by the expertise of the user. Fans are expected to be over-informed and highly enthusiastic in their possession of knowledge about the objects of their passions and thus able to provide details of all kinds. In the case of graphic design, this could assist in revealing when, where, by whom, for what purpose, and in what medium something was produced. Many graphic design artifacts are often created in an office, with a team that might include an art director, designer, photographer, illustrator, printer, or any number of other people. In community settings, much of this labor might be taken on by individuals who have professional careers. Having information about these people provides insight into a wide range of practices. An entire hidden history of production and reception could be made visible through tagging.

But other features of a work, such as its iconography or style can also be called out. Imagine a graphic with individuals carrying protest signs surrounded by tactical squads and police dogs. What to tag? The place and date? Themes of the signs? Animal rights and police tactics? In a collection as large as PGDA, the needle in a haystack analogy is barely sufficient to describe the challenge of finding anything in particular. Browsing, searching, and looking through search results are informative, but finding something specific is much harder. So, for example, suppose you were looking for examples of paragonnage, the technique of using mixed sizes and styles of fonts in a single form. Could you search PGDA for them? The term is not even familiar to most readers, so finding the tag paragonnage might not open an avenue of productive inquiry. For usual or rare items to be found and tagged, the community would need to cooperate the way birding groups do when they focus on rare sightings—record them when they occur. This is a “see something, tag something” approach to creating useful metadata. But it is also an argument for making tag lists available to users for common application.

Making tags useful

Tags that identify designers, studios, fonts, periods, styles and so on are very useful for researchers. Artists, editors, publishers, political leaders, and other participants in community production benefit from being named and recognized. Calling attention to something that is an early or unknown work by someone, or an unusual use of a font, or anything that can be identified with expert knowledge and strikes your eye is helpful. While it might seem that highly detailed or specific tags are best, keep in mind that the term might not occur to a researcher or browser. Tagging content so that several levels of classification are identified is the most useful: advertising + Chicago + Johnson Publishing offers three points of entry at different levels of specificity. This supports searches from the most general to the more specific. Even if the tags are not organized hierarchically and in pathways, conceiving the group of tags attached to a specific image or object in this way provides the highest probability of usefulness.

Keep in mind that the function of tags is to add knowledge, but also, to call objects to attention for those who would not find them otherwise. Be both generic and specific. Tags are also doing work of interpretation, not merely identification. Affective tags and those that have an expressive dimension are gaining traction even among information professionals. So characterizing something as “bad design” or “brash Dayglo” could serve a purpose. Keep in mind that the Archive is a public space, however, where protocols of civility are respected.

To reiterate, what makes for useful tags are specific terms: the designer, the studio, the date. These are fundamental categories for design research. Many more idiosyncratic features of objects might be of interest. You may know something very specific. For instance, is a poster interesting because of the band? A musician? Is an image something made by a photographer or artist whose career should be noted? Is the font a quirky variant? But most of all, it is important to make use of individual knowledge and interests. Is the work relevant to the history of queer communities, feminism, activism, a newsworthy event, or a local situation?

Classification and identification

The most important aspect of tagging is that if a feature is named, it can be found. Imagine going through a stack of documentary photos where a print shop you once worked in shows someone at a small offset press, another person at a light table, and someone loading newspapers on a palette for shipping. If these are tagged, the information remains attached. Crowd-sourced tagging has become increasingly common in online local history archives. Tags participate in and build relations with other tags and categories. Though PGDA appears as a flat system—all tags exist at the same level and are displayed in one long stream—conceptually they embody the pathway described above from most general to most specific. Ultimately, the presentation of tags might benefit from being organized into a classification scheme as an alternate way to access both their content and the objects to which they are attached.

The discussion of classification schemes is a topic that consumes considerable oxygen in the information world, particularly among those who are invested in the way knowledge organization functions. The very structure of classification embodies decisions, value judgments, and of course biases, but is also a fascinating thought experiment. Should designers be listed under studios and firms? Should projects be listed under design firms or should firms be listed as the higher category? What about patrons and sponsors? Do you want to find all of the work done for the Berkeley Barb or search by individuals and see what publications they were contributing to in that same time period and place?

Idiosyncratic expertise

Tagging is an act of generosity that requires just a bit of reflection about what level of detail to communicate. Idiosyncratic information is the most useful. What you know best someone else knows least. But keep in mind that some users will only search at the most general level, the “top” level of “General Description.” Be sure a high-level tag is always present on an object—and if it belongs to more than one, add the tag. Try to make the meaning of tags clear and unambiguous. This will support its being used again by someone else. If it isn’t clear, let it be provocative. Vague tags won’t be repurposed, and endlessly proliferating tags can create other problems at scale. If a tag already exists that works, use it. Add detail in addition if that adds to identification. “Fairy tale images” is going to be more useful than “Little Red Riding Hood,” but the two together are the most helpful. “Woman” is going to produce too many hits. Does “stylish woman” have any kind of meaningful content? What tags describe substantive categories and which only point to attributes? All can be useful, but keep the principle of general-to-detailed categories in mind.

Values and judgements

On another level, tags serve to define the intellectual parameters of a field. By giving something a name, you establish a class or category. Did anyone ever before imagine calling something “wild” or “salacious” or characterize it as part of “conceptual” work? When does it become apparent that something is “radical,” “racist,” or “biased” in its style and contents? Knowledge classification embodies and expresses values. These shift and change as the grounds of judgment change over time. Eventually, the PGDA tag set will be its own contribution to cultural history, a repository of terminology and assessments, language styles and attitudes, as well as an endlessly useful tool for navigating the Archive.