PoWOWer to the People!

WOW! That was pretty much my daily reaction when I started researching California’s contribution to graphic design that resulted in my 2014 book, Earthquakes, Mudslides, Fires & Riots: California and Graphic Design, 1936–1986. By the time that the book was finished, I’d spent over ten years of WOW! WOW! WOW!

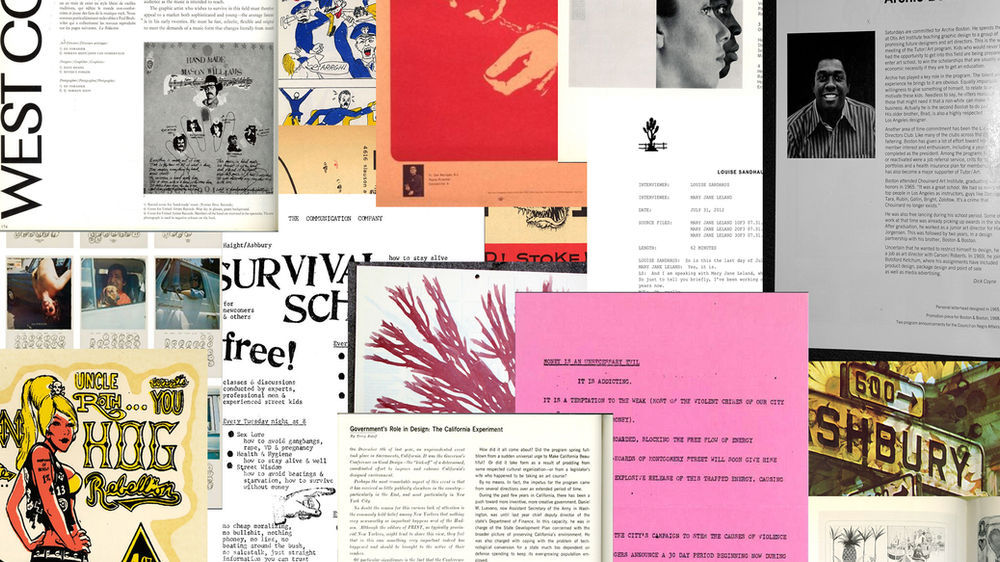

In the end it was clear that I’d opened a vast Pandora’s box of graphic design history—one that for me challenged conventional notions of what graphic design history was, aka “the canon.” But it was also clear that I’d just scratched the surface of what was out there; I’d revealed one tiny hue in an infinite rainbow and there was so much more to be discovered. Besides that, I was just one person with a singular point of view looking through both a microscope and telescope at my own galaxy of interests.

It also dawned on me that I was probably among a handful of researchers with the time and resources to delve into this infinity of material—stuff stashed in attics and basements, and all the stories about the lives and experiences of the people who had made this work that would likely end up in dumpsters. This was all too clear to me when I discovered the whereabouts of the AIGA Los Angeles archive just weeks after it had been tossed. Also, there had been so much content that didn’t make into Earthquakes now gathering pixel dust.

In the early 2010s LACMA announced it would start to collect graphic design and I began to contemplate what they might collect. How would this venerable institution represent the vastness of this everyday art—one that’s vital in representing an infinitude of cultures used to inform, to protest, to educate and to sell, as well as to delight and inspire. I imagined the challenges that the museum would have trying to figure out how best to represent graphic design. Would it just be the canon, or would they confront what belongs in the category of graphic design in the first place? Would they recognize historical works that hadn’t been acknowledged? And would they recognize the fragrant garden in their own back yard—graphic design from Los Angeles? I wondered if work by designers from the past who were never featured in the design press or documented would be “discovered.” For example, John and Marilyn Neuhart belong in this category. They produced a profound body of design work yet little of it has been seen. Also deserving a nod are such forgotten or nearly forgotten designers as Marion Sampler, a Black designer who worked for Gruen Associates, an LA design studio that in the 1960s was known for its racial and gender inclusivity. Or Group Five who produced thousands of genre record cover designs. Who, you say? Exactly my point.

Then there’s design for the alternative press and protest graphics in the sixties and seventies that was created by designers without formal training using cheap or readily available tools driven by an incredible passion to get a message out. There is also the work that came directly out of print shops—some of which have gained more recent attention such as the Majestic and Colby poster shops. And I’m just talking about the print media that’s been in the shadows. What about title design for film and television? Industrial films and light shows. The list is endless.

It 2016 I wrote, but never sent, a rather cheeky letter to LACMA. Here’s how it went:

Dear LACMA,

May I respectfully suggest setting up a program with local higher education institutions for students studying art history, film history, or graphic design to work with aging designers to organize and identify their work. Legendary title designer Pablo Ferro is living in a garage with boxes filled with reels of his work that are unidentified. Same goes for Gere Kavanaugh. And there as so many others. An alternative approach to preserving this history has to be figured before it’s too late and this gold is gone.

Along those lines, provide instruction on how to do an oral history and provide an informal digital repository to which the interviews can be uploaded.

Why not keep going. How else are you going to discover new “masterpieces”? Provide the tools and means (and get the word WAY out there to many audiences) to get others to share stuff they know about or have discovered. Yes it’ll be the Wild West but perhaps the recent revamp of The Walker’s website making it an aggregator of content rather than generator of content is a model. To avoiding a free-for-all of whatever crap, they hired an editor/curator to solicit and sort.

That’s my quick two cents. Good luck LACMA!

p.s. I’m offering a class this fall for graphic designers entitled Making History. Perhaps we should chat.`

This was the genesis story of The People’s Graphic Design Archive. At least the rough concept: Make discovering and expanding graphic design history a crowd-sourced effort. Let it be messy.

Much has happened since a first inkling a very different graphic design history that began in Lorraine Wild’s Historical Survey of Graphic Design classes at CalArts but most significantly along the way I’ve worked with so many incredibly thoughtful and dedicated colleagues and students who were my partners and allies.

There were some fits and starts along the way, but a breakthrough came when I approached Silas Munro, a former student who had gone on to accomplish much with his own graphic design history research. Out of mutual need for a community to provide support and feedback, together we founded Design History Fridays, a group of design educators, historians, writers and curators, all of whom were expanding and challenging conventional graphic design history. The benefits of the group are countless, but the bonanza was the connection I made with Briar Levit and Brockett Horne who are now my partners in The People’s Graphic Design Archive.

Another fit and start was identifying a platform that would allow crowd-sourcing. We looked at off-the shelf options, the considerably expensive blue-sky route of a custom-built platform, and then finally realized that an excellent model was staring us in the face: Fonts In Use and their team Nick Sherman, Stephen Coles and Rob Meek. They are now our project partners in developing the permanent site.

There’s some fundraising to go in order to build our final home, but the momentum is definitely there and thanks to the capabilities of Notion, the initiative is up and running. Notion, a collaborative platform for gathering all sorts of data, allows us to test the concept and build the databases that later can be exported to The People’s Graphic Design Archive custom platform when it’s completed.

The bottom line is that The People—anyone who has an interest—should decide what belongs as part of graphic design history. Contributions can be entire research projects (I’m currently uploading all the research done for Earthquakes), a single image, a link to archive; a fact, an anecdote; a small collection; the stash your neighbor has from their mother’s career as a commercial artist, a typesetter, or a printer. Anything. Everything. I think the history that will result will be messy, open-ended, crazily diverse, representing many points of view, interests, concerns. I anticipate it’ll be years to come of shock and awe at what design history—our collective cultures—actually looks like. And lots of WOW WOW WOW!