Changing the Paradigm for how Graphic Design Histories are Taught

In 2021, I was hired by George Mason University to redesign the Graphic Design History course to reflect the needs of our students and the world in which they now find themselves. Continuing the status quo was no longer an option. The students demanded more, expected more, and deserved more than a regurgitation of the same narratives and limited perspectives preserved in the single lone voice of a default textbook based on a stale historical canon.

A new era in graphic design education was beginning to take hold in American universities led by educators and practitioners that demanded a different idea of what design could be, how it could look, who could make it, and how it could function in society. A new framework needed to be built.

In 2019, before I was hired at Mason, I collected writings and lectures in hopes of teaching design history in a more complex, and nuanced manner. The new course would give students a broader historical context of how design functions through critical analysis and a diverse array of viewpoints.

I began to see myself more as a steward of information and wanted to remove (as much as possible) the hierarchy from the classroom. It also was important that the students knew this was not going to be a typical classroom or lecture, but a community where they could exchange ideas and share their thoughts freely in an open and safe space. It was also vital that students be given the freedom to make their own discoveries and have agency in their education.

Speaking with Briar Levit, an Associate Professor at Portland State University, helped me build a solid foundation for the class. Over the summer, I shared my vision for the new design history class with three students. Their involvement was integral to my learning about what they wanted and expected from a design history course. What was clear — they did not want to sit through an entire 2-hour and 40-minute class of me lecturing from a book. They expressed the desire to learn from a diverse group of people while being active participants in the classroom through discussion, and they still wanted to learn about the traditional canon. Students should be given the opportunity to question what they learn and the role that design has played in labor, capitalism, and production, as well as think deeply about the impact each design movement and theory has had on society, weighing the potential strengths and drawbacks. Critical thinking skills are not just important for designers. The reality is that some of our students will not pursue design careers after school and will find their calling elsewhere (my class is open to non-design majors). I like to believe that we aren’t just graduating designers but complex thinkers who can navigate a complex world. These skills they begin to develop will carry over into whatever they decide to do.

From their feedback, I was able to refine the goals, content, and structure of the class and break it down into four sections:

1. Traditional canon

Students pair up to give a presentation on a chapter from the book, Graphic Design, A New History. This is an opportunity for students to understand the traditional canon and learn how to work together as a team to improve their research and presentation skills.

2. Analysis and criticism of the traditional canon by learning about design history from different perspectives and reclaiming minority and marginalized design histories

After the students gave their presentation, we read an essay or watched a video together, as a class, about design history from perspectives that are not included in the book. For example, during one class, students presented “Chapter 8, The Triumph of the International Style,” and afterward, we read “Long Live Modernism” by Massimo Vignelli, “Against, but in the Spirit of Modernism,” by Jerome Harris, and watched his 2019 Typographics lecture, “Who’s Bad.” This is where the shift starts from the single-story narrative to offering various perspectives. This allows for more productive, open, and engaging class discussions. During another class, we watched “The Missing Chapters: Black Women in Graphic Design” by Tasheka Arceneaux-Sutton and read her essay, “Where are the Black Graphic Designers at CalArts?”

Students are also responsible for a weekly written response of their choice from a diverse list of readings, lectures, movies, or podcasts Briar and I have collected. For example, students can watch “The Quiltmakers of Gee’s Bend,” “Iro: The Essence of Color in Japanese Design,” or a short documentary, “Pen & Pixel.” They can also read ”The Life of Huang Hua Cheng, the Idiosyncratic Designer Who ‘Led Taiwan into the First Design Revolution’” or “The Queen of Arab Cover Design.” Each of these choices introduces students to deeper aspects of design history that are not included in any single textbook.

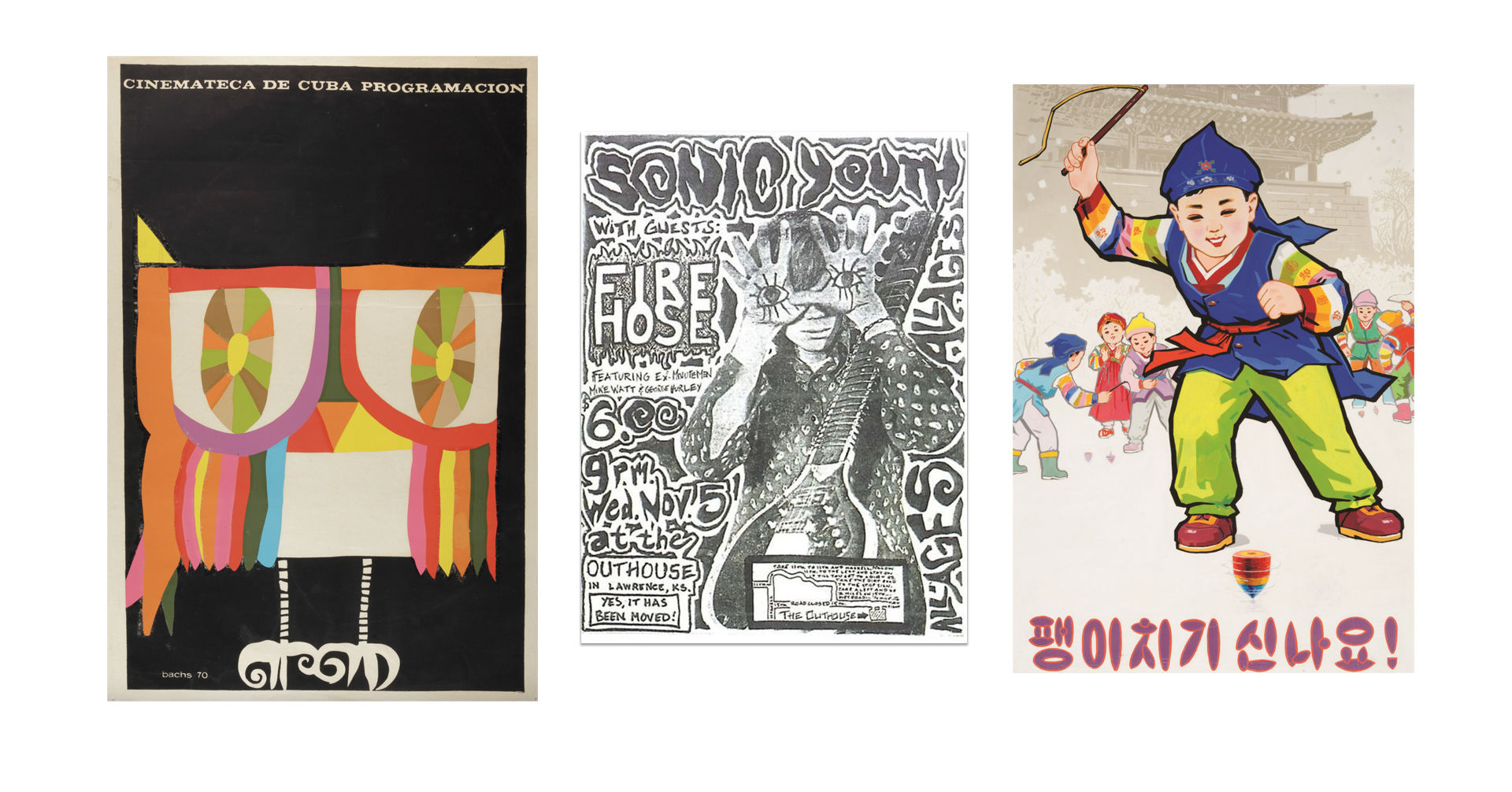

Items researched by students and added to The People's Graphic Design Archive. Left: Eduardo Muñoz Bachs, Cinemateca de Cuba programación, 1970 (Discovered by Freddie Enomoto); Center: Jason Willis, Sonic Youth show flyer, 1986 (Discovered by Sophia Truxell-Svenson and Kendall Reed); Right: North Korea Propaganda poster, “Spinning Tops is Fun!” (Discovered by Alyssa Chandler and Marissa Lustan).

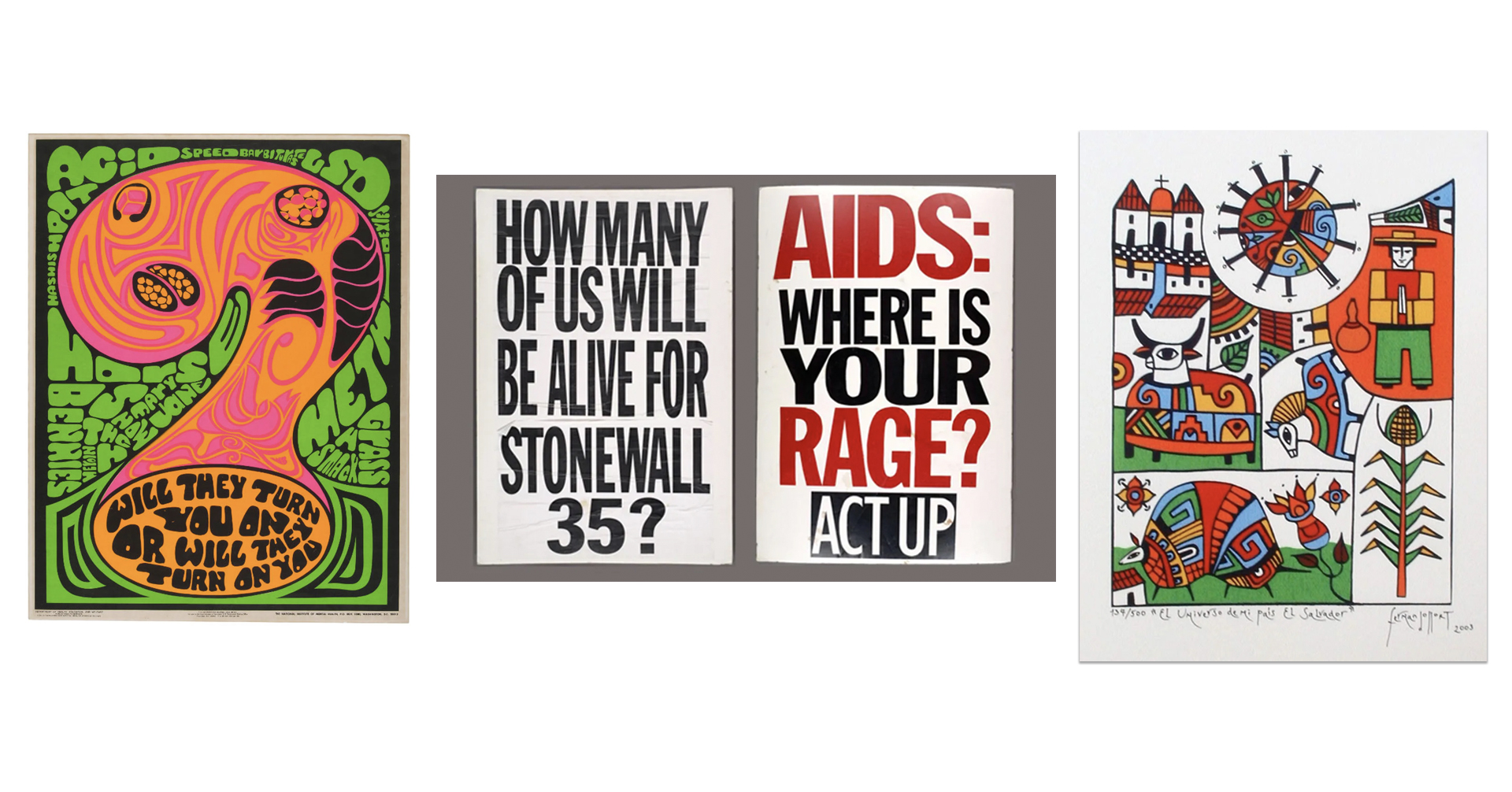

3. Investigating, researching, and documenting lost and forgotten histories with The People’s Graphic Design Archive

Students partner up and search for examples of graphic design that they feel should be documented and part of the archive. Students love this part of the class because they can get together with their friends and be active participants in documenting design history. When all the groups have finished uploading their findings to the PGDA, each group gives a short presentation to the class on what they have found. This puts students at the center of the class and in a position to educate everyone, including me.

The significance of this exercise is not lost on the students. One of my students, for example, commented on this activity in one of his weekly written responses that he did on “Preserving Syrian Design History and Graphics in the Arab world: Meet the Syrian Design Archive” by Jyni Ong. Jahmel Pope wrote:

Overall, this article presents an interesting case for why independently run digital archives are so important. Full disclosure: until this reading, the People’s Graphic Design Archive group assignment always puzzled me on what purpose it had for my graphic design education. Reading this article helped me better understand the importance of this weekly activity as we are not only broadening our own appreciation for design, but we are also aiding in the preservation of an overlooked part of art history that would otherwise be forgotten, making this art more accessible for future generations of artists to learn from, just like Kinda and her colleagues.

Items researched by students and added to The People's Graphic Design Archive. Left: US National Department of Health, Education, and Welfare anti-drug poster, 1970 (Discovered by Zainab Samsudeen); Center: Double-sided ACT UP Poster, 1995 (Discovered by Luke Rahman); Right: Fernando Llort, Universo de Mi Pais El Salvador, 2003 (Discovered by Marly Saravia).

4. Research paper

This is a semester-long project due on the last day of class. This project gives students the opportunity to formulate their own research papers driven by their individual interests. On the last day of class, each student gives a short presentation on their research. Undertaking these presentations adds to the feeling of community in the class and empowers everyone to learn from each other. Currently, one student is researching Scandinavian sewing traditions, and another is documenting graphic design history from her native country of Sri Lanka.

This curriculum is by no means complete nor do I believe it should ever feel complete — it should be dynamic, responsive, and ever-evolving in concert with recent insight, research, and opinions as they become available. There should be no reason to continue to rely on a single lineage when there is such a large amount of diverse information available to us now than ever before when all we had to rely on previously was the dogmatic voice of a lone textbook. Our collective design history is a multicultural, heterogeneous fabric that has been woven together throughout time by different ethnicities across the globe, and what we teach our students should reflect that.

Discovering and applying new perspectives helps us innovate and evolve as educators and allows us to cooperate with one another and meaningfully contribute to our shared history alongside our students.

Alan Caballero LaZare is a Colombian American educator and Assistant Professor of Graphic Design at George Mason University where he teaches Graphic Design History and Visual Communication Theories.

@cabalazaa on Instagram

cabalaza.com

Featured image Sochi protest wall mural, 2014, by ChrisFleming (IDa4). Researched and added to The People's Graphic Design Archive by Michael Rojas-Davilla and Natalie McCarter.